Shadows animated with imperfect, jerky movements on the white surface. The black silhouette of a flat, 2D puppet took shape. It was a woman, presumably a nurse, with a tall distinctive medieval hat like I had seen on the models in one of the other rooms. She approached a second puppet lying horizontal on a bed with the restlessness of illness. She administered some indistinguishable treatment. Likely it was something illogical, reflecting the gut-churning lack of understanding of medical science in a time when they were needed as much as any other in Europe’s long history. Crude sound effects emanated from behind the small theater. The puppeteer’s gentle, precision movements showed compassion from the nurse as she carefully tended to the terminal patient.

Shadows animated with imperfect, jerky movements on the white surface. The black silhouette of a flat, 2D puppet took shape. It was a woman, presumably a nurse, with a tall distinctive medieval hat like I had seen on the models in one of the other rooms. She approached a second puppet lying horizontal on a bed with the restlessness of illness. She administered some indistinguishable treatment. Likely it was something illogical, reflecting the gut-churning lack of understanding of medical science in a time when they were needed as much as any other in Europe’s long history. Crude sound effects emanated from behind the small theater. The puppeteer’s gentle, precision movements showed compassion from the nurse as she carefully tended to the terminal patient.

The whole scene unfolded on a white sheet suspended from the side of one of the very distinct four-post beds that formed a row the length of the large room. Bobby walked with captivation, gazing at the theater as though under a mild trance, and took a seat on the stone floor next to his sisters. The puppet show was something I devoted no more than ten seconds of thought to as I strolled about the old hospital. In fact, I was about to gather the crew to continue our tour in the next rooms when I witnessed their interest. It’s impossible to predict what will draw them in.

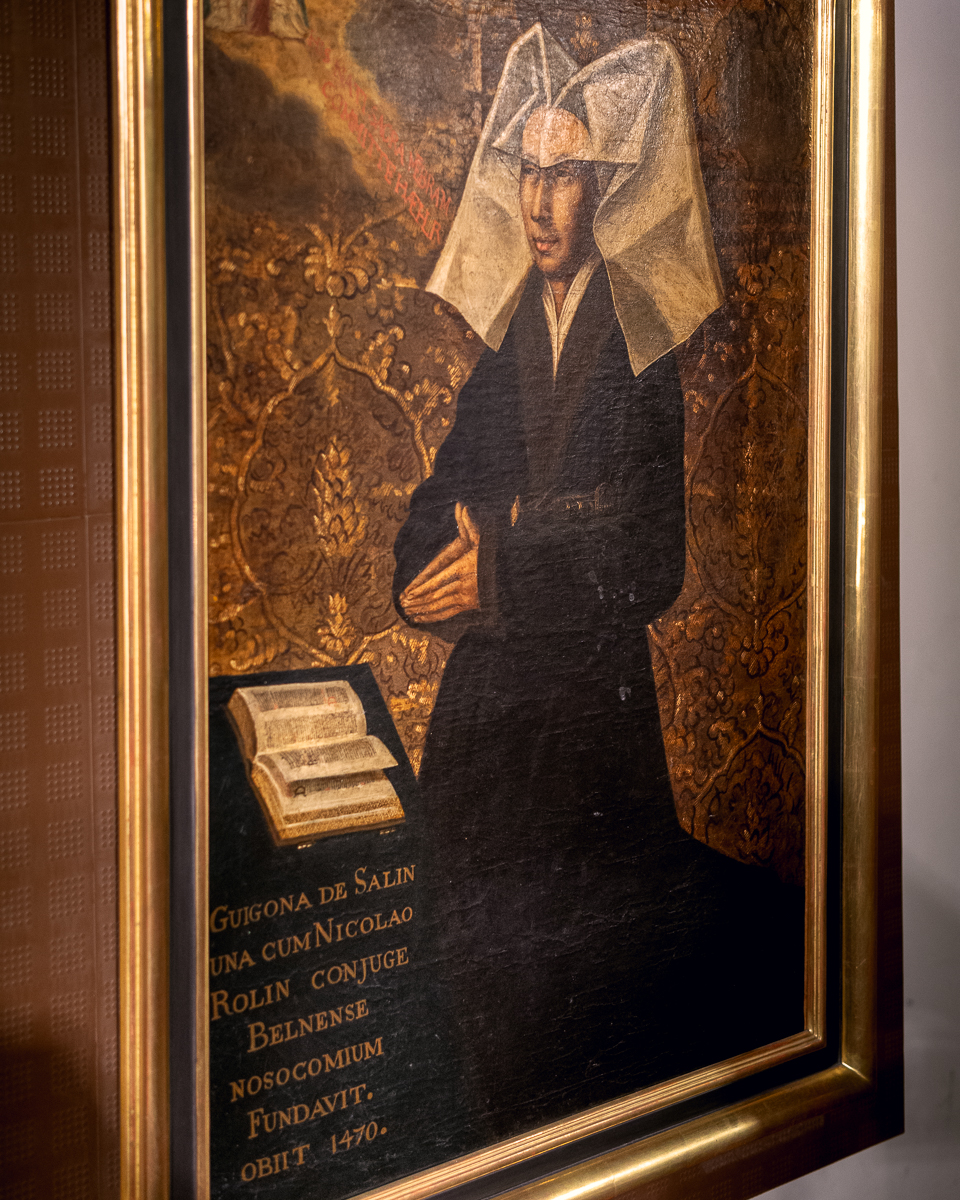

The sick-bed puppet show was an effective tool in bridging the gap between our modern world and the events that happened in this very special building seven centuries earlier. The Hospices de Beaune or Hôtel-Dieu de Beaune is the true gem of the city. It was a private hospital founded in 1443 as an act of good-faith to care for victims of the Plague and the recently ended Hundred Years War. Beaune was devastated and the Hôtel-Dieu was, in truth, a place for the poor to die in the good graces of God. The museum was a fascinating tribute to the challenging realities of life in late-Middle-Ages France. But the hospital is equally celebrated today for its physical beauty as for its compassionate use.

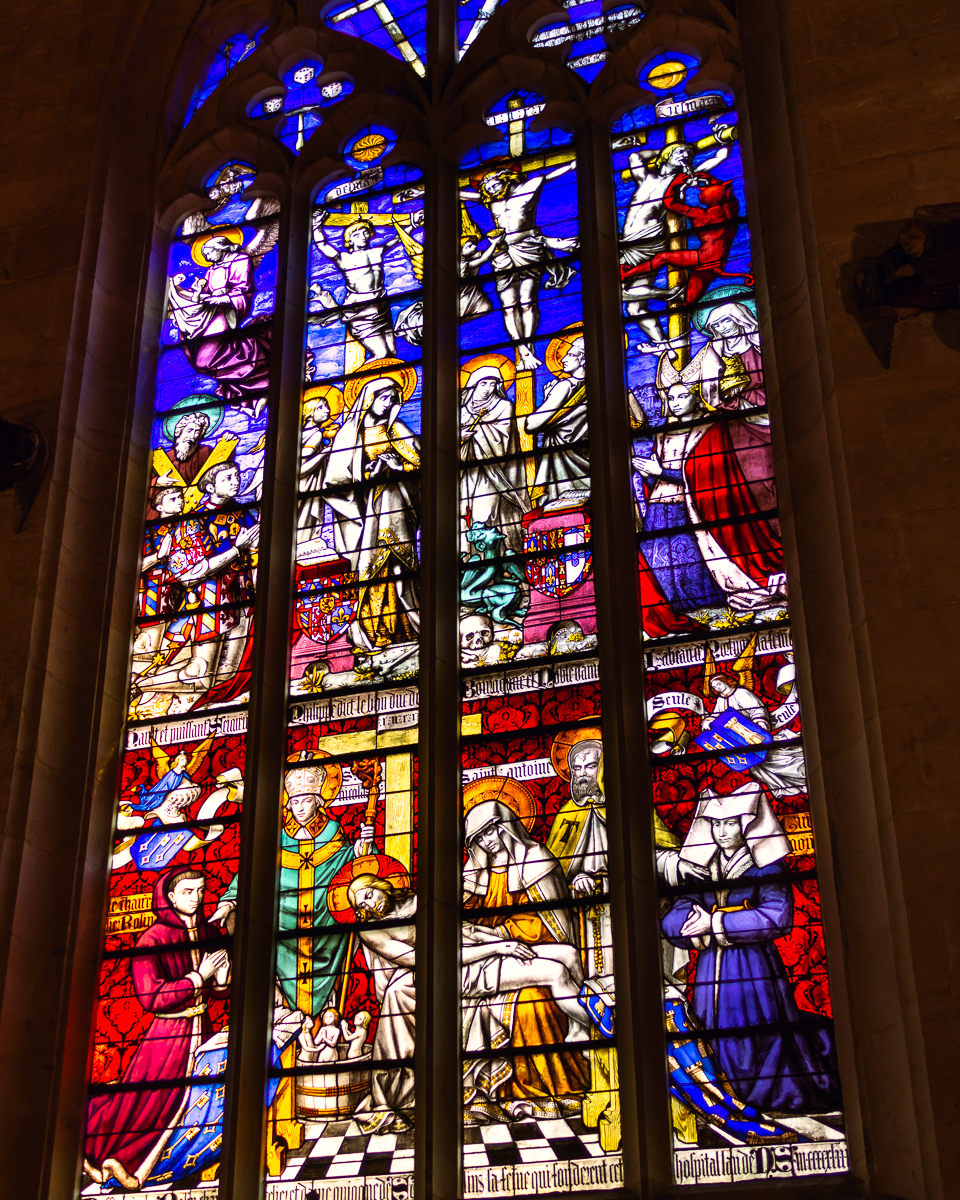

Truly unique in construction, the complex more resembles a monastery of the time than maybe anything else. The exterior is simple with austere stone, while the courtyard is rich with exuberant wood and an elaborate, tall and brightly-tiled roof. It’s a dichotomy of contrasts in a single structure like I’ve not seen elsewhere. So architecturally important the Hôtel-Dieu had a full chapter carved out in my university Art History curriculum. The value of the service it provided to the region, though, surpassed even its artistic contributions and cannot be understated. And the breadth of its longevity is staggering as it remained in constant use up through WWI where it served to treat those many artillery-mangled men.

Thankfully, for we modern visitors, the Hôtel-Dieu’s inexorable beauty and unprecedented history have ensured its perfect preservation. There was no line to get in, and there were only a handful of others exploring the complex. I took time to appreciate this and envisioned what high season might look like. Expecting to be racing through the stone halls with disinterested kids, I spent little to no effort learning much about the history myself, beyond what Lydia had read to us from her journal. I couldn’t have miscalculated more. The kids entered the facility with every bit as much interest as the next person. They engaged with the exhibits. They asked surprisingly pertinent questions, and they took great care in learning about what they were seeing. At times we even waited for them to finish exploring before we moved on, like with the puppet show.