Out the front door of the apartment, north across the pedestrian street and an access road barely large enough for a car to turn around, stood a peculiar gated passage. Crossing through the swinging chrome gate was like stepping into a portal. It zigged and zagged through buildings with staircases and balconies that were situated at irregular Escher-like angles. A menacing roaring sound grew with every step. It sounded so violent that I treaded lighter and lighter looking for its source. From far below the pavement a torrent of water gushed through a weir and down the foreshortening river in the distance. It was startling enough that I stepped back from the railing. In moments, we were spit through a matching chrome gate and into a magical gingerbread wonderland on the opposite side.

Restaurants with awning-shaded patios squeezed already narrow, cobbled streets. Their sagging buildings were criss-crossed by wooden beams and vining growth with blooms of all colors. Our location was mysterious and it wasn’t clear if we were on an island or a bridge or solid ground. There were a number of finger-like appendages with man-made embankments, and they were connected by a maze of bridges that crossed waterways shooting in every direction.

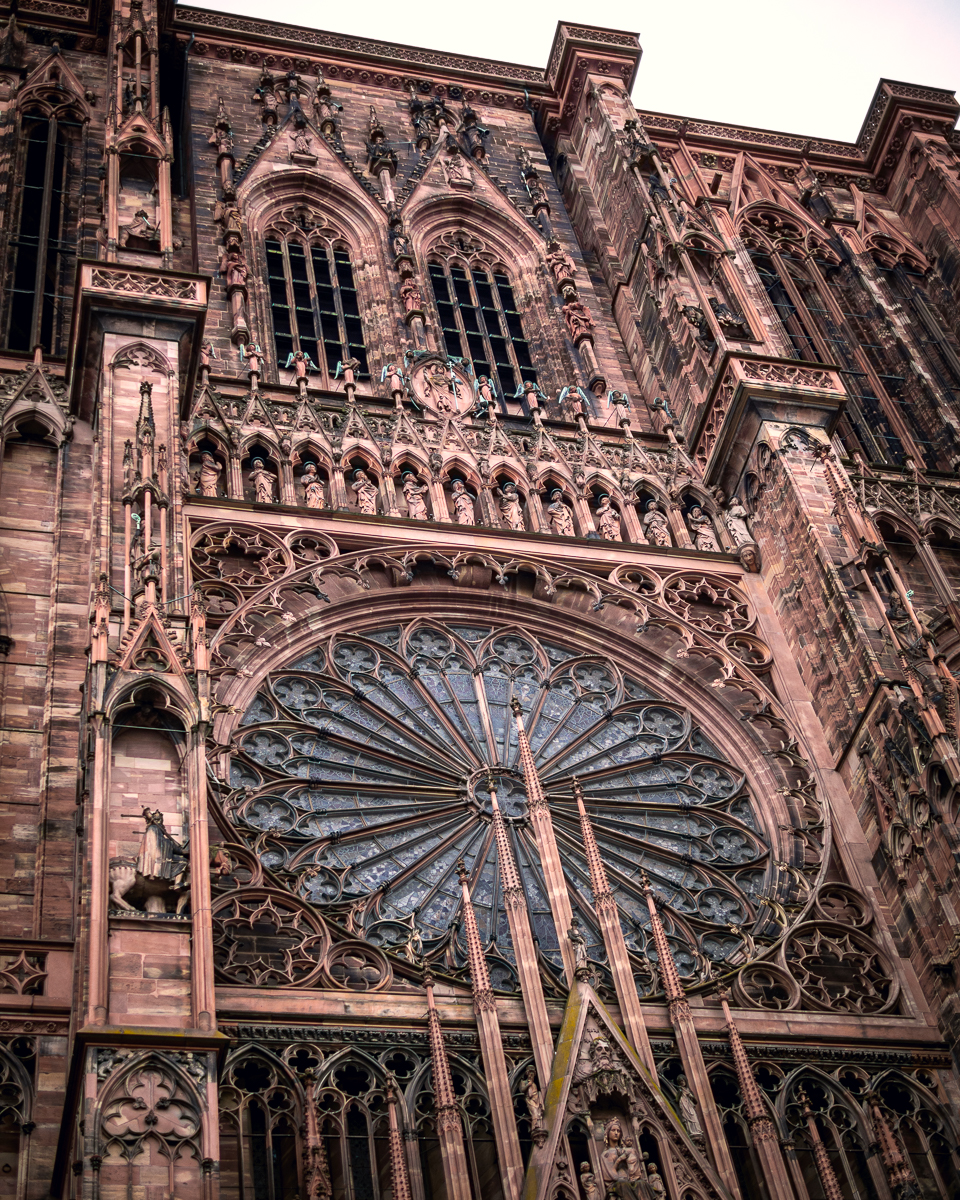

Strasbourg is in the same cultural and architectural vein as Colmar but more than three times larger and immediately far easier on the eyes. It’s sophisticated and a city that’s much more comfortable in its own skin than Colmar. It’s the capital and largest city of the greater Grand Est region that stretches from Germany west to Paris, and it’s the most important city I’d never hear of. Strasbourg is both historic and modern. It’s a youthful university city and also home to the European Parliament. To say that Strasbourg has been forever defined by war would be grossly understated. Centuries of push and pull between the Germans and the French had put it in a perpetual crossfire, and it spent its fair share of time belonging to each country. Today, they embrace the role of peacemaker and haven’t minced words blaming the stupidity of Europe’s leaders for war and suffering.

While I gawked at its beauty, Amanda quickly walked to the first building we encountered. It was the most attractive structure in sight, which said a lot. Ivy and greenery dreamily covered most of the building and large letters reading Au Pont Saint-Martin were nearly fully concealed. Explosions of red and while flowers burst from boxes that hung on heavy wooden beams and tiers of deep and secluded balconies cascaded down to river level. It was occupied by a dense and dark restaurant with heavy wooden furniture and panelling and a vaguely nautical theme. It was not entirely French and not entirely German.

Through a forest of weighty beams and red checkered tablecloths, a wall of monstrous five-story, half-timber buildings could be seen across the rapidly moving river. These however, weren’t the cute-as-a-button, Hansel and Gretel type. They were more of an oddball construct with strange rooflines and balconies and were clearly not designed with architectural beauty as a priority. This was the tanners’ row, a medieval industrial wasteland with easy access to the river for dumping toxic waste. Hides were once hung for drying on the peculiar balconies, and I found it remarkable that this industrial area had survived the centuries.