Two beautiful restaurants with tables adorned in white clothes flanked the mouth of the peculiar road that lay ahead of us. One of them bore ornate decorations from its elegant boulangerie past. Both were closed and preparing for the dinner hour. The leafy pedestrian lane meandered upward beyond their purview and disappeared into a narrow passage in the distance. It possessed all the hallmarks of a small French village devoid of any city planning. The crude cobbled street retained medieval Paris’ original grade and somehow managed to escape Haussmann’s bulldozers. It was irregular and sloped with broad, shallow steps, and I immediately knew their construction was to accommodate travel on horseback. On the hill to the left, the imposing gothic church of Saint-Gervais-et-Saint-Protais rose high and commanding from behind natural old-growth vegetation. Colorful, irregular red and blue facades zigged and zagged up the jaunty street and blue and yellow tables from a cafe spilled down the incline like strewn stones on a garden path.

Earlier we had left Notre Dame to prepare for its concert. We had traversed the web of bridges that connect Île de la Cité and Île Saint-Louis. A few restaurants and cafes converged on their pointed ends, and we peaked in the door of the restaurant Saint Regis, wishing, longingly, that there was a table for five available. But there was not. Undeterred, we crossed the river once again to the right bank and found ourselves transported to a part of the city that modern Paris seemed to have forgotten.

This ancient and beloved hidden street in the Marais is called Rue des Barres. Its old cobblestones and historic mansions act as a window into 17th century Paris, now only a wistful distant memory elsewhere in the city. At the edge of this time-defying neighborhood, around a right-hand elbow in the narrow passage, stand two of Paris’ only remaining timber homes. They lean on each other, unmolested and unrecognized, as they have for centuries, surely bearing witness to an unparalleled multitude of events.

In the shadow of the church, one of the larger blue tables was unoccupied. We quickly procured it as assured as if we had called in a reservation. An attractive middle aged couple sat in front of the blue paneled facade of the restaurant in content silence and sipped small glasses of red wine. The man read a newspaper while the woman gazed out at the sparse passing pedestrian traffic. Flanking the entrance a young family was dining with friends. The mother rocked a baby in a modern rugged stroller and the father delicately passed small bites of food by his lips, directing his gaze to the quiet setting while savoring the meal.

Lydia commented that she was cold, and she had the hood of her rain jacket cinched tight around her face. The air still bore a chill that forced us into the only coats we possessed. But the bright late-afternoon sky had evacuated the morning’s storm clouds, and it wasn’t so cold to chase us inside. For June, however, it was downright frigid. The young waiter pulled down the chalk menu board that hung on the wall outside the open door. We would be ordering a la carte from the small French-language-only menu.

It was 6 PM and this cafe had been serving all day. Traditional restaurants like the two at the bottom of the lane are only open at precise dining hours – usually 11:30-2:00, 7:30-10:00. Bistros are as well, though provide a much more casual experience. Brasseries are generally larger than Bistros and more like French pubs and serve food all day. The most iconic of all Parisian establishments however are cafes. Cafes are local coffee shops typically with their distinctive small tables and woven chairs tightly smooshed together on sidewalk patios facing the activity on the streets. Cafes serve drinks and light fare and snacks and are open all day and evening.

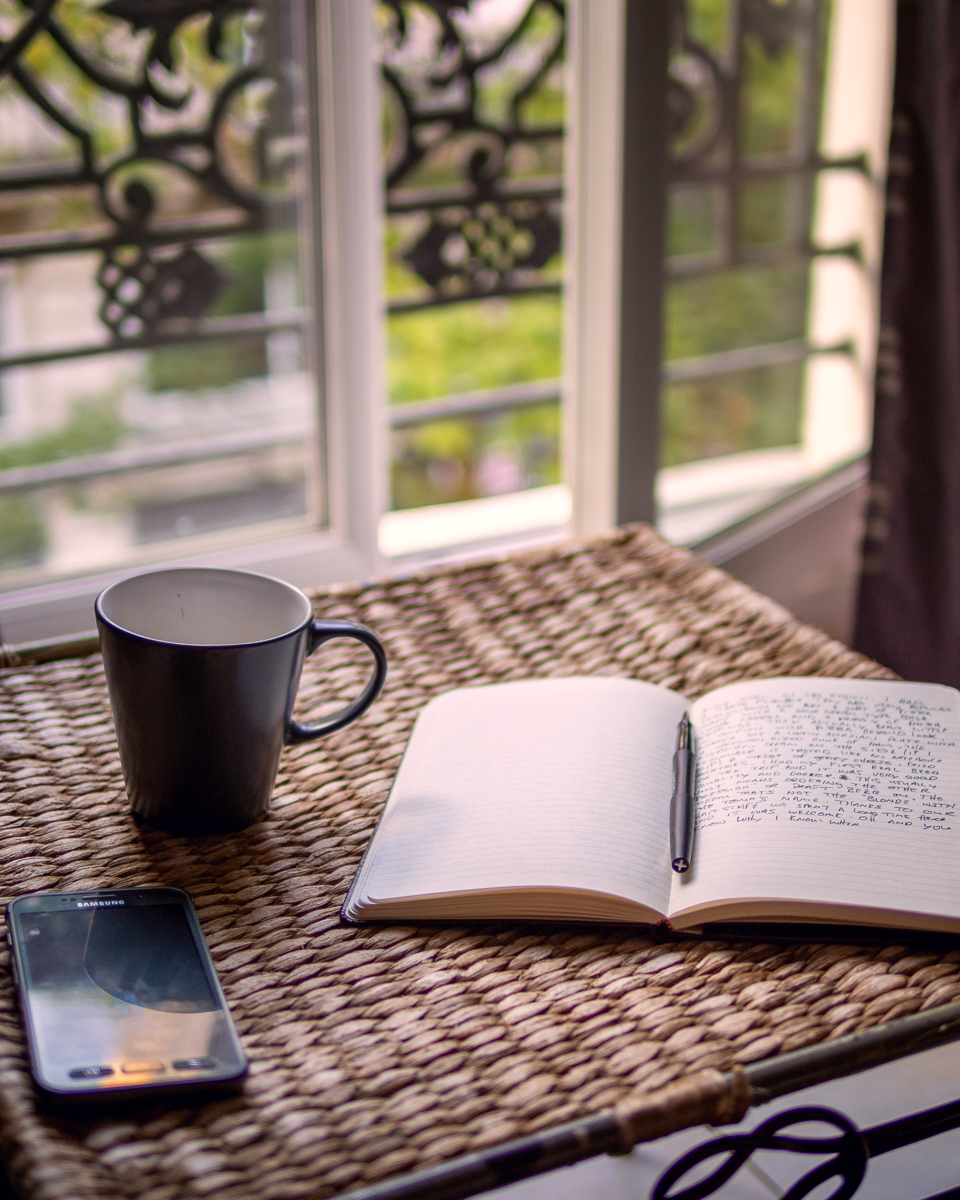

I pulled out my phone to record a video and asked Lydia to reflect on all we had seen. She spoke about art and the scavenger hunt and the prizes. She described the new Parisian clothes she got from the department store and talked about the views of the Eiffel Tower from the rooftop. She explained that it had been rainy and cold and how she couldn’t wait for the eggs and bread she had ordered. The twins were much too distracted to contribute anything useful when I directed the camera on them.

The waiter spoke English, but it made no difference as we were now armed with our survival French and two week of intensive practice. We ordered proudly and we would have been unrecognizable as the same people fumbling at the crepe shop on day one. As the twins sipped milk from their stemmed glass mugs, Amanda was plating the divided omelet and small salad that they would be sharing on an extra plate. There are no children’s menus in Paris like there were in Alsace, but there were always plenty of options. I was surprised, however, when Gigi asked for milk and the waiter didn’t hesitate to bring her a glass. This, I am told, is rare.

When the waiter placed the very tall and magazine-worthy quiche Lorraine before me, Lydia, by far the hungriest of all, was already dipping her baguette into the yoke of the two fried eggs that shared a plate with a colorful seasonal salad. On the table in front of Amanda was an obscenely decadent, heaping plate of smoked salmon, blinis and cream. Once again she would “win” dinner, albeit narrowly, and received more than willing help from the whole table in finishing it.